Health, Fitness,Dite plan, health tips,athletic club,crunch fitness,fitness studio,lose weight,fitness world,mens health,aerobic,personal trainer,lifetime fitness,nutrition,workout,fitness first,weight loss,how to lose weight,exercise,24 hour fitness,

Labels

Technology

New Post

These high-fibre vegan sticky date protein cookies will give you a boost of energy

from Nutrition | body+soul https://ift.tt/2YzZNbN

Chrissy Teigen has ignited an internet debate over the ‘right’ way to cook eggs

from Nutrition | body+soul https://ift.tt/3lucKy3

Long naps may be bad for health

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/2QxO2y9

Spit in a tube to diagnose heart attack

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/3hx9j7c

Obesity linked with higher risk for COVID-19 complications

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/3aZg6UE

Unique HIV reservoirs in elite controllers

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/31xfLFP

How 'swapping bodies' with a friend changes our sense of self

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/34B9VVC

Link between cognitive impairment and worse prognosis in heart failure patients

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/2YBnJvr

Novel alkaline hydrogel advances skin wound care

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/2EyB7JV

NBA playoff format is optimizing competitive balance by eliminating travel

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/3jtvoUX

How are information, disease, and social evolution linked?

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/32puWjC

Seizures during menstrual cycle linked to drug-resistant epilepsy

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/2YzzgLQ

Fear of missing out impacts people of all ages

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/2Qnxau2

Is it safe to reduce blood pressure medications for older adults?

“Doctor, can you take away any of my medications? I am taking too many pills.”

As physicians, we hear this request frequently. The population most affected by the issue of being prescribed multiple medications, known as polypharmacy, is the elderly. Trying to organize long lists of medications, and remembering to take them exactly as prescribed, can become a full-time job. In addition to the physical and emotional burden of organizing medications, older adults are at increased risk for certain types of side effects and potential worse outcomes due to polypharmacy.

A common source of prescriptions is high blood pressure, with older adults often finding themselves on multiple medications to lower their blood pressure. Data from the Framingham Heart Study show that over 90% of middle-aged people will eventually develop high blood pressure, and at least 60% will go on to take medications to lower blood pressure.

The OPTIMISE trial, recently published in JAMA, studied the effect of reducing the number of blood pressure medications, also known as deprescribing, in the elderly.

How low should blood pressure be in older adults?

Previous large studies, including the HYVET trial and the more recent SPRINT trial, have shown that treatment of high blood pressure in older adults remains important, and may reduce the risk of heart attack, heart failure, stroke, and cardiovascular death. Black adults made up 31% of the SPRINT trial study population; therefore, study results could be used to make recommendations for this population, which is at increased risk for high blood pressure. However, many groups of older people were excluded, including nursing home residents, those with dementia, diabetes, and other conditions common in more frail older adults.

The most recent guidelines from the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA), published in 2017, define optimal blood pressure as less than 120/80 for most people, including older adults age 65 or above. They recommend a target of 130/80 for blood pressure that is treated with medication. The 2018 guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) recommend a more relaxed goal of less than 140/90.

The US and European populations differ in their risk for cardiovascular disease, with the US population generally considered at higher risk for strokes, heart failure, and heart attacks, so it might be appropriate to have different blood pressure goals for these two groups. Regardless, both groups acknowledge that factors such as frailty, limited life expectancy, dementia, and other medical issues should be considered when developing individualized goals for patients.

What happened to older patients whose blood pressure medications were reduced?

The OPTIMISE trial provided preliminary evidence that some older adults may be able to reduce the number of blood pressure medications they take, without causing a large increase in blood pressure. For the trial, researchers randomized 569 patients age 80 or older, with systolic blood pressure lower than 150 mm Hg, to either remain on their current blood pressure medications, or to remove at least one blood pressure medication according to a prespecified protocol. The study subjects were followed for 12 weeks to assess blood pressure response.

Researchers found that both the people who remained on their previous blood pressure medications and those who reduced the number of medications had similar control of blood pressure at the end of the study. While the mean increase in systolic blood pressure for the group that reduced medications was 3.4 mm Hg higher than the control group, the number of patients who had systolic blood pressure below the goal of 150 mm Hg at the end of the study was not significantly different between groups. Approximately two-thirds of patients were able to remain off the medication at the end of the study.

It is important to note that OPTIMISE is relatively a small study, and the investigators did not examine long-term outcomes such as heart attack, heart failure, or stroke for this study (as the HYVET and SPRINT trials did), so we don’t know what the long-term effect of deprescribing would be.

More research needed to examine long-term effects of deprescribing

While the OPTIMISE trial was promising, larger and longer-duration trials looking at outcomes beyond blood pressures alone are necessary to really know whether deprescribing is safe in the long term. Additionally, these researchers used a target systolic blood pressure of less than 150 mm Hg, which is higher than the most recent ACC/AHA and ESC/ESH recommendations.

An interesting aspect of this study design is that the primary care physician had to feel that the patient would be a good candidate for deprescribing. This left room for physicians, who may know patients well, to individualize their decisions regarding deprescribing.

The bottom line

This trial gives doctors and other prescribers some support when considering a trial of deprescribing a blood pressure medication for select older patients, with a goal to improve quality of life. These patients must be closely followed to monitor their responses.

The post Is it safe to reduce blood pressure medications for older adults? appeared first on Harvard Health Blog.

from Harvard Health Blog https://ift.tt/32nsaLA

Unlocking the mysteries of the brain

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/32sHfvl

Pollution exposure at work may be associated with heart abnormalities among Latinx community

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/3gtfl7C

Depressed or anxious teens risk heart attacks in middle age

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/34zXEB1

Hip fracture risk linked to nanoscale bone inflexibility

from Top Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/32n3Edw

Hip fracture risk linked to nanoscale bone inflexibility

from Women's Health News -- ScienceDaily https://ift.tt/32n3Edw

Michelle Bridges’ latest activewear drop for Big W is the GOODS

from Fitness | body+soul https://ift.tt/34FWAeC

New Research Confirms Statins Are Colossal Waste of Money

The lecturer in the featured video, Maryanne Demasi, Ph.D., produced the 2014 Australian Catalyst documentary, "Heart of the Matter: Dietary Villains," which exposed the cholesterol/saturated fat myths behind the statin fad and the financial links which lurk underneath.

The documentary was so thorough that vested interests actually convinced ABC TV to rescind the two-part series.1 The Australian Heart Foundation, the three largest statin makers (Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Merck Sharp & Dohme) and Medicines Australia, Australia's drug lobby group, complained2 and got the documentary expunged from ABC TV.

Cholesterol and saturated fat have been the villains of heart disease for the past four decades, despite the many studies showing neither has an adverse effect on heart health.

The entire food industry shifted away from saturated fat and cholesterol, ostensibly to improve public health, and the medical industry has massively promoted the use of cholesterol-lowering statin drugs for the same reason. Despite all of that, the rate of heart disease deaths continues to be high.3 That really should tell us something.

Statins Are a Colossal Waste of Money

Since the release of Demasi's documentary, the evidence against the cholesterol theory and statins has only grown. As noted in an August 4, 2020, op-ed by Dr. Malcolm Kendrick, a general practitioner with the British National Health Service:4

"New research shows that the most widely prescribed type of drug in the history of medicine is a waste of money. One major study found that the more 'bad' cholesterol was lowered, the greater the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, almost every other medical condition has been shoved onto the sidelines. However, in the UK last year, heart attacks and strokes (CVD) killed well over 100,000 people — which is at least twice as many as have died from COVID-19.

CVD will kill just as many this year, which makes it significantly more important than COVID-19, even if no one is paying much attention to it right now."

According to a scientific review5 published online August 4, 2020, in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, lowering LDL is not going to lower your risk of heart disease and stroke. "Decades of research has failed to show any consistent benefit for this approach," the authors note.

Since the commercialization of statin drugs in the late '80s (lovastatin being the first one, gaining approval in 19876), total sales have reached nearly $1 trillion.7,8 Lipitor — which is just one of several brand name statin drugs — was named the most profitable drug in the history of medicine.9,10 Yet these drugs have done nothing to derail the rising trend of heart disease.

Lowering Cholesterol Does Not Show a Beneficial Impact

According to a press release announcing the BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine review, the analysis found that:11

"… over three quarters of all the trials reported no positive impact on the risk of death and nearly half reported no positive impact on risk of future cardiovascular disease.

And the amount of LDL cholesterol reduction achieved didn't correspond to the size of the resulting benefits, with even very small changes in LDL cholesterol sometimes associated with larger reductions in risk of death or cardiovascular 'events,' and vice versa. Thirteen of the clinical trials met the LDL cholesterol reduction target, but only one reported a positive impact on risk of death …"

In their paper,12 the study authors argue that since dozens of randomized controlled trials looking at LDL-cholesterol reduction "have failed to demonstrate a consistent benefit, we should question the validity of this theory."

They also cite the Minnesota Coronary Experiment,13 a double-blind randomized controlled trial involving 9,423 subjects that sought to determine whether replacing saturated fat with omega-6 rich vegetable oil (corn oil and margarine) would reduce the death rate from heart disease by lowering cholesterol.

It didn't. Mortality and cardiovascular events increased even though total cholesterol was lowered by 13.8%. For each 30 mg/dL reduction in serum cholesterol, the death risk rose by 22%. In conclusion, the Evidence-Based Medicine study authors note that:14

"In most fields of science the existence of contradictory evidence usually leads to a paradigm shift or modification of the theory in question, but in this case the contradictory evidence has been largely ignored, simply because it doesn't fit the prevailing paradigm."

Deception Through Statistics

If lowering cholesterol doesn't reduce mortality or cardiovascular events, there's little reason to use them, considering they come with a long list of adverse side effects. Sure, there are studies claiming to show benefit, but many involve misleading plays on statistics.

One common statistic used to promote statins is that they lower your risk of heart attack by about 36%.15 This statistic is derived from a 2008 study16 in the European Heart Journal. One of the authors on this study is Rory Collins, who heads up the CTT Collaboration (Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' Collaboration), a group of doctors and scientists who analyze study data17 and report their findings to regulators and policymakers.

Table 4 in this study shows the rate of heart attack in the placebo group was 3.1% while the statin group's rate was 2% — a 36% reduction in relative risk. However, the absolute risk reduction — the actual difference between the two groups, i.e., 3.1% minus 2% — is only 1.1%, which really isn't very impressive.

In other words, in the real world, if you take a statin, your chance of a heart attack is only 1.1% lower than if you're not taking it. At the end of the day, what really matters is what your risk of death is the absolute risk. The study, however, only stresses the relative risk (36%), not the absolute risk (1.1%).

As noted in the review18 "How Statistical Deception Created the Appearance That Statins Are Safe and Effective in Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease," it's very easy to confuse and mislead people with relative risks.

You can learn more about absolute and relative risk in my 2015 interview with David Diamond, Ph.D., who co-wrote that paper. Research questioning the veracity of oft-cited statin trials is also reviewed in "Statins' Flawed Studies and Flawed Advertising."

Statins Sabotage Your Health

A stunning review of statin trials published in 2015 found that in primary prevention trials, the median postponement of death in those taking statins was a mere 3.2 days. While potentially extending life span by 3.2 days, those taking statins are also at increased risk for:

|

Diabetes (if taken for more than two years, your risk for diabetes triples) |

Dementia, neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric problems such as depression, anxiety and aggression |

|

Musculoskeletal disorders |

Osteoporosis |

|

Cataracts |

Heart disease |

|

Immune system suppression |

Oftentimes statins do not have any immediate side effects, and they are quite effective, capable of lowering cholesterol levels by 50 points or more. This is often viewed as evidence that your health is improving. Side effects that develop over time are frequently misinterpreted as brand-new, separate health problems.

Crimes Against Humanity

The harm perpetuated by the promotion of the low-fat, low-cholesterol myth is so significant, it could easily be described as a crime against humanity. Ancel Keys' 1963 "Seven Countries Study" was instrumental in creating the saturated fat myth.19,20

He claimed to have found a correlation between total cholesterol concentration and heart disease, but in reality this was the result of cherry picking data. When data from 16 excluded countries are added back in, the association between saturated fat consumption and mortality vanishes.

In fact, the full data set suggests that those who eat the most saturated animal fat tend to have a lower incidence of heart disease, which is precisely what other, more recent studies have concluded.

Procter & Gamble Co.21 (the maker of Crisco22), the American Heart Association and the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) all promoted the fallacy for decades, despite mounting evidence that Keys had gotten it all wrong.

The AHA was issuing stern warnings against butter, steak and coconut oil as recently as 2017.23 That same year, Procter & Gamble partnered with University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute to promote heart health by lowering cholesterol.24

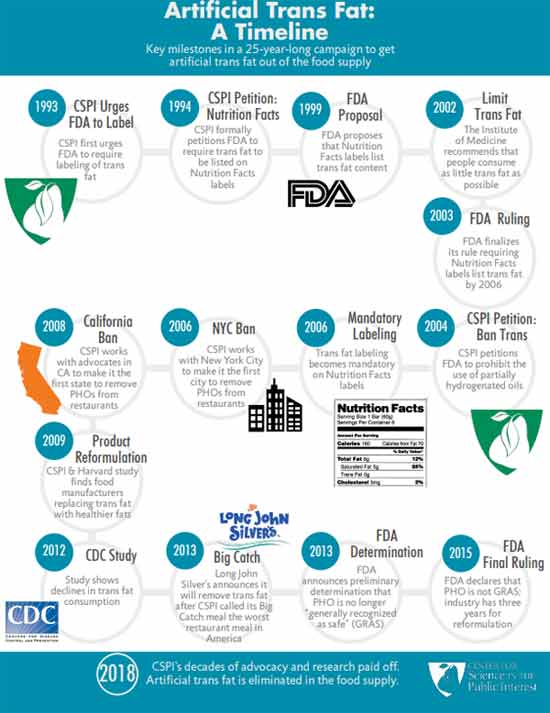

CSPI was also instrumental in driving heart disease skyward with its wildly successful pro-trans fat campaign. It was largely the result of CSPI's campaign that fast-food restaurants replace beef tallow, palm oil and coconut oil with partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, which are high in synthetic trans fats linked to heart disease and other chronic diseases.

As late as 1988, CSPI praised trans fats, saying "there is little good evidence that trans fats cause any more harm than other fats" and that "much of the anxiety over trans fats stems from their reputation as 'unnatural.'"25

CSPI and AHA Omit Their Role in Heart Disease Epidemic

Today, you'll have to dig deep to unearth CSPI's devastating public health campaign. In an act of deception, they erased it from their history to make people believe they've been doing the right thing all along. Their historical timeline26 of trans fat starts at 1993 — the year CSPI decided to change course and start supporting the elimination of the same trans fat they'd spent years promoting.

Similarly, the AHA conveniently omits saturated fat and cholesterol from its history of "lifesaving" breakthroughs and achievements.27 It makes sense, though, considering the AHA's and CSPI's recommendations to swap saturated fat for vegetable oils and synthetic trans fat never resulted in anything but an epidemic of heart disease.

The idea that the harms of trans fats were unknown until the 1990s is simply a lie. The late Dr. Fred Kummerow started publishing evidence showing trans fat, not saturated fat, was the cause of heart disease in 1957. He also linked trans fat to Type 2 diabetes. You can click on this link to watch my interview with him. I traveled to his home in Urbana, Illinois, shortly before he passed away.

The Truth About Saturated Fat

In addition to the more recent studies mentioned earlier, many others have also debunked the idea that cholesterol and/or saturated fat impacts your risk of heart disease. For example:

• In a 1992 editorial published in the Archives of Internal Medicine,28 Dr. William Castelli, a former director of the Framingham Heart study, stated:

"In Framingham, Mass., the more saturated fat one ate, the more cholesterol one ate, the more calories one ate, the lower the person's serum cholesterol. The opposite of what … Keys et al [said] …"

• A 2010 meta-analysis,29 which pooled data from 21 studies and included 347,747 adults, found no difference in the risks of heart disease and stroke between people with the lowest and highest intakes of saturated fat.

• Another 2010 study30 published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that a reduction in saturated fat intake must be evaluated in the context of replacement by other macronutrients, such as carbohydrates.

When you replace saturated fat with a higher carbohydrate intake, particularly refined carbohydrate, you exacerbate insulin resistance and obesity, increase triglycerides and small LDL particles, and reduce beneficial HDL cholesterol. According to the authors, dietary efforts to improve your cardiovascular disease risk should primarily emphasize the limitation of refined carbohydrate intake, and weight reduction.

• A 2014 meta-analysis31 of 76 studies by researchers at Cambridge University found no basis for guidelines that advise low saturated fat consumption to lower your cardiac risk, calling into question all of the standard nutritional guidelines related to heart health. According to the authors:

"Current evidence does not clearly support cardiovascular guidelines that encourage high consumption of polyunsaturated fatty acids and low consumption of total saturated fats."

Will Saturated Fat Myth Soon Be Upended?

To learn more, be sure to listen to Dr. Paul Saladino's interview with Nina Teicholz, previously featured in "Why Chicken Is Killing You and Saturated Fat Is Your Friend."

Teicholz, a science journalist, adjunct professor at NYU's Wagner Graduate School of Public Service and the executive director of The Nutrition Coalition, is also the author of "The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet," which reviews the many myths surrounding saturated fat and cholesterol.

In the interview, Saladino and Teicholz review the history of the demonization of saturated fat and cholesterol, starting with Keys, and how the introduction of the first Dietary Guidelines for Americans in 1980 (which recommended limiting saturated fat and cholesterol) coincided with a rapid rise in obesity and chronic diseases such as heart disease.

Teicholz also reviews a paper32 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, published online June 17, 2020, which actually admits the long-standing nutritional guideline to limit saturated fat has been incorrect. This is a rather stunning admission, and a huge step forward. As noted in the abstract:

"The recommendation to limit dietary saturated fatty acid (SFA) intake has persisted despite mounting evidence to the contrary. Most recent meta-analyses of randomized trials and observational studies found no beneficial effects of reducing SFA intake on cardiovascular disease (CVD) and total mortality, and instead found protective effects against stroke.

Although SFAs increase low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, in most individuals, this is not due to increasing levels of small, dense LDL particles, but rather larger LDL which are much less strongly related to CVD risk.

It is also apparent that the health effects of foods cannot be predicted by their content in any nutrient group, without considering the overall macronutrient distribution.

Whole-fat dairy, unprocessed meat, eggs and dark chocolate are SFA-rich foods with a complex matrix that are not associated with increased risk of CVD. The totality of available evidence does not support further limiting the intake of such foods."

from Articles https://ift.tt/2EFmq7B

via IFTTT

Study of Heart Attack Victims Showed Most Had Normal LDLs

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), or heart disease, is a term that refers to several types of heart conditions. Many of the problems associated with heart disease are related to atherosclerosis. This term refers to a condition in which there's a buildup of plaque along the walls of the artery, making it more difficult for blood to flow and for oxygen to reach the muscles, including the heart.

This can be the underlying problem in cases of heart attack, stroke and heart failure. Other types of CVD happen when the valves in the heart are affected or there's an abnormal heart rhythm.1

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. and it contributes to other leading causes including stroke, diabetes and kidney disease.2 It also ranks as the No. 1 cause of death around the world: Four out of five deaths are from heart attack or stroke.3

Heart disease accounts for 25% of deaths in the U.S. with a $219 billion price tag, based on data from 2014 to 2015.4 Scientists believe some of the key contributing factors are high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, physical inactivity and excessive alcohol use.

Cholesterol Levels in People Who Had Heart Attacks

There is ongoing disagreement over the levels at which cholesterol presents a risk for heart disease and stroke. Added to this, many doctors and scientists continue to recommend lowering fat consumption and using medications to lower cholesterol levels.

A national study from the University of California Los Angeles showed that 72.1% of the people who had a heart attack did not have low-density (LDL) cholesterol levels, which would have indicated they were at risk for CVD. Their LDL cholesterol was within national guidelines and nearly half were within optimal levels.5

In fact, half the patients admitted with a heart attack who had CVD had LDL levels lower than 100 milligrams (mg), which is considered optimal; 17.6% had levels below 70 mg, which is the level recommended for people with moderate risk for heart disease.6

However, more than half the patients who were hospitalized with a heart attack had high-density lipoproteins (HDL) in the poor range, based on a comparison to national guidelines.

The team used a national database with information on 136,905 people who received services from 541 hospitals across the U.S. They were admitted between 2000 and 2006 and, while they had their blood drawn upon arrival, only 59% had their lipid levels checked at that time.

Of those who were checked, out of everyone who was admitted with a heart attack but didn’t have CVD or Type 2 diabetes, 72.1% had LDL levels less than 130 mg/dL, which was the recommended level at the time of the study (2009).

In addition to this, researchers found the levels of HDL cholesterol (the “good” kind) had dropped compared to statistics from earlier years, with 54.6% having levels below 40 mg/dL.7 The desirable level for HDL is 60 mg/dL or higher.8

The findings led researchers to suggest that the guidelines for prescribing cholesterol medication should be adjusted — to lower the number at which drugs should be administered. In other words, they are suggesting that more people be put on cholesterol drugs. As explained by Dr. Gregg C. Fonarow, lead investigator:9

"Almost 75 percent of heart attack patients fell within recommended targets for LDL cholesterol, demonstrating that the current guidelines may not be low enough to cut heart attack risk in most who could benefit."

The study was sponsored by the Get with the Guidelines program that's supported by the American Heart Association, which promotes the use of statins for lowering LDL cholesterol.10 Fonarow has done research for GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer, and has consulted for, and received honoraria from Merck, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Abbott — all of which manufacture cholesterol drugs, including statins.

Cholesterol Myth May Be Kept Alive by Big Pharma

While scientists and physicians continue to investigate the level of cholesterol that may affect heart attack risk, the theory that dietary cholesterol is a contributor has long been proven false. In the 1960s it may have been a conclusion that researchers made based on the available science, but decades later the evidence does not support the hypothesis.11

Yet, as some researchers have pointed out, the move toward removing dietary cholesterol limits has been slow. In the past 10 years, some have modified recommendations to address certain negative consequences of limiting dietary cholesterol, such as the risk of having inadequate levels of choline. Unfortunately, others have continued to promote low-fat diets and that could have hazardous results.

Whether discussing cholesterol intake or serum cholesterol levels, the data do not support the hypothesis that it relates to heart disease. I believe it appears that the evidence supporting the use of cholesterol-lowering statin drugs is likely little more than the manufactured work of pharmaceutical companies.

This also appears to be the conclusion of the authors of a scientific review published in the Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology.12 The team identified significant flaws in three recent studies: “… large reviews recently published by statin advocates have attempted to validate the current dogma. This article delineates the serious errors in these three reviews as well as other obvious falsifications of the cholesterol hypothesis.”

The authors present substantial evidence that total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol are not indicators of heart disease risk. In addition, statin treatment is doubtful as a form of primary prevention. In their analysis, they point out that if high cholesterol levels were a major cause of atherosclerosis, patients with high total cholesterol whose levels were lowered the most by statin drugs should see the greatest benefit. However, evidence does not show that to be the case.

In another review of statin trials and other studies in which cholesterol was linked to heart disease, researchers could not find a correlation between cholesterol and the degree of coronary atherosclerosis, coronary calcification or peripheral atherosclerosis. They found no exposure response in which those with the highest level of cholesterol enjoyed the greatest benefit from reduction.13

These researchers propose the link between high LDL or total cholesterol and heart disease may be secondary to other factors that promote CVD, such as:14

“… lack of physical activity, mental stress, smoking, and obesity. It is generally assumed that their effect on cardiovascular disease is mediated through the high cholesterol, but this may be a secondary phenomenon.

Physical activity may benefit the cardiovascular system by improving endothelial function, or by stimulating the formation of collateral vessels; mental stress may have a harmful influence on adrenal hormone secretion, smoking increases the oxidant burden; in these all situations the high cholesterol may be an epiphenomenal indicator that something is wrong.”

Saturated Fat Is Crucial but Vegetable Oil Is Deadly

One of the reasons so many people are sick is that we’re constantly told that animal fats are unhealthy and industrial vegetable oils are not, and people believe it. The authors of a recent paper in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology admits the long-standing nutritional guideline to limit saturated fat is incorrect.

This is a tremendous step forward in righting a dietary wrong that started with Ancel Keys’ flawed hypothesis15 and has since had a significant impact on health and wellness. As the researchers note in the abstract:16

“The recommendation to limit dietary saturated fatty acid (SFA) intake has persisted despite mounting evidence to the contrary. Most recent meta-analyses of randomized trials and observational studies found no beneficial effects of reducing SFA intake on cardiovascular disease (CVD) and total mortality, and instead found protective effects against stroke.

Although SFAs increase low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, in most individuals, this is not due to increasing levels of small, dense LDL particles, but rather larger LDL particles, which are much less strongly related to CVD risk. It is also apparent that the health effects of foods cannot be predicted by their content in any nutrient group without considering the overall macronutrient distribution.

Whole-fat dairy, unprocessed meat, and dark chocolate are SFA-rich foods with a complex matrix that are not associated with increased risk of CVD. The totality of available evidence does not support further limiting the intake of such foods.”

In a recent speech at the Sheraton Denver Downtown Hotel, titled "Diseases of Civilization: Are Seed Oil Excesses the Unifying Mechanism?" Dr. Chris Knobbe revealed evidence that seed oils, so prevalent in modern diets, are the reason for most of today's chronic diseases.17

His research charges the high consumption of omega-6 seed oil in everyday diets as the major unifying driver of the chronic degenerative diseases so prevalent in modern civilization.

He calls the inundation of Western diets with harmful seeds oils "a global human experiment … without informed consent." You’ll find more, including a video of his presentation in “Are Seed Oils Behind the Majority of Diseases This Century?”

Your Omega-3 Index Is More Predictive Than Cholesterol

The combination of a diet high in omega-6 fats commonly found in vegetable oils and low in omega-3 fats, commonly found in fatty fish, is yet another risk factor for coronary heart disease. As the National Institutes of Health describes:18

"The three main omega-3 fatty acids are alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). ALA is found mainly in plant oils such as flaxseed, soybean and canola oils. DHA and EPA are found in fish and other seafood."

Each of the three fats plays a unique role in cellular health. The authors of one study analyzed the risk of a cardiovascular event while taking icosapent ethyl.19 The medication is a "highly purified omega-3 fatty acid" that is "a synthetic derivative of the omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)."20

Those who took the medication had a significantly lower number of ischemic events than those taking the placebo. An omega-3 deficiency leaves you vulnerable to chronic disease and lifelong challenges. The best way to determine if you're getting enough is to be tested, as it’s a good predictor of all-cause mortality.21

The omega-3 index is a measure of the amount of EPA and DHA in red blood cell membranes. This has been validated as a stable and long-term marker because it reflects your tissue levels. An index greater than 8% is associated with the lowest risk of death, while an index lower than 4% places you at the highest risk of heart disease-related mortality.22

Your best sources of fatty fish are wild-caught Alaskan salmon, herring, mackerel and anchovies. The larger predatory fish, such as tuna, have much higher amounts of mercury and other toxins. It's important to realize your body can’t convert enough plant-based omega-3 to meet your needs. That means that if you're a vegan, you must figure out a way to compensate for the lack of marine or grass fed animal products in your diet.

If your test results are low, and you are considering a supplement, compare the advantages and disadvantages of fish oil and krill oil. Krill are wild-caught and sustainable, more potent than fish oil and less prone to oxidation. You’ll find more about the benefits of maintaining adequate levels of omega-3 fats in “Omega-3 Index More Predictive Than Cholesterol Levels.”

Know Your Cholesterol Ratios

The cholesterol myth has been a boon to the pharmaceutical industry since cholesterol-lowering statins have become some of the more frequently prescribed and used drugs. In a report by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force published in JAMA, evidence showed that 250 people need to take a statin drug for one to six years to prevent one death from any cause.23

When measuring cardiovascular death specifically, 500 would have to take a statin drug for two to six years to prevent even one death. As the evidence mounts that statin drugs are not the answer and simple cholesterol levels may not help you understand your risk of heart disease, it's time to use other risk assessments.

In addition to an omega-3 index, you can get a more accurate idea of your risk of heart disease using an HDL/total cholesterol ratio, triglyceride/HDL ratio, fasting insulin level, fasting blood sugar level and iron level. You’ll find a discussion of the tests and measurements in “Cholesterol Does Not Cause Heart Disease.”

from Articles https://ift.tt/32oDK9b

via IFTTT